Chasing Charlotte and catching the light in the Côte d’Azur

Searching for the places where one of my favorite artists, Charlotte Salomon, created her work "Life? or Theatre?" and reflecting on what it means to create art

What makes you shape and reshape yourselves so brightly from so much pain and suffering? Who gave you the right?

— Overlay on the first epilogue painting of Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? (Leben? oder Theater?)

I saw the strangest, most beautiful thing the other week. I was out walking early one morning before I left Madrid, and I decided to sit down on a park bench and drink my coffee for a bit. As I was sitting there, a disheveled man carrying a bunch of bags walked up and began to settle down on the bench across from me. I watched as he carefully unfolded four very sturdy boxes and placed them in a neat line in front of his bench. He then put a bunch of delicate plastic bags on the seat next to him and sat down to eat a loaf of bread. After every bite he took for himself, he tore off a piece and threw it to the birds that gathered by his feet, sharing with them half of what little he had.

But then he began to do something even more strange, and even more delightful. Slowly, he rose from the bench and began to shake out and smoothen each one of the plastic bags that he had piled next to him. Then, selecting one after some consideration — although they all looked identical to me — he walked out into the center of the empty street and began to wave the bag through the air like a kite.

He had walked directly into a stream of sunlight, where the morning rays created a molten spotlight through the trees. His plastic bag floated above him like a toy soldier’s parachute. It seemed as though he had a technique to this bag waving, as he would twirl the bag just so up until it reached a particular angle that inflated it completely with air, and then gracefully turn the bag again. It floated through the air like the rhythmic underwater dance of a jellyfish — it was beautiful. He was paying me absolutely no mind, so I stared blatantly and freely, mouth wide open. He was an actor, and the street was his stage. After a while he took the bag, still inflated with air, and stored it in the first of the boxes. Then he repeated the whole process again and again.

After the third or fourth time, I suddenly realized what he was trying to do: catch and store the first light of day.

The whole time I was observing this, I never thought that this man was acting outside the realm of sanity by any metric; rather, I viewed him as some sort of performance artist. And it made me think about what the act of creating art really means. Maybe this thing I saw in a city park in Madrid was actually an example of the work that all artists, at the heart of their creation process, are trying to do: simply attempting to catch the light.

When my Fulbright ended in June, I left Madrid to travel around Europe as safely as I could within the constraints of a pandemic-stricken world. One place I had always wanted to go was Nice in the Côte d’Azur, in part because it was a place that had greatly inspired many of my favorite artists — Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Raoul Dufy, George Braque, and the artist upon whose work I centered my thesis: Charlotte Salomon. It is the experience of being in the place in which that last artist, Charlotte Salomon, created her life’s work, Life? or Theatre?, while in hiding from the Nazis, that I would like to reflect upon briefly here.

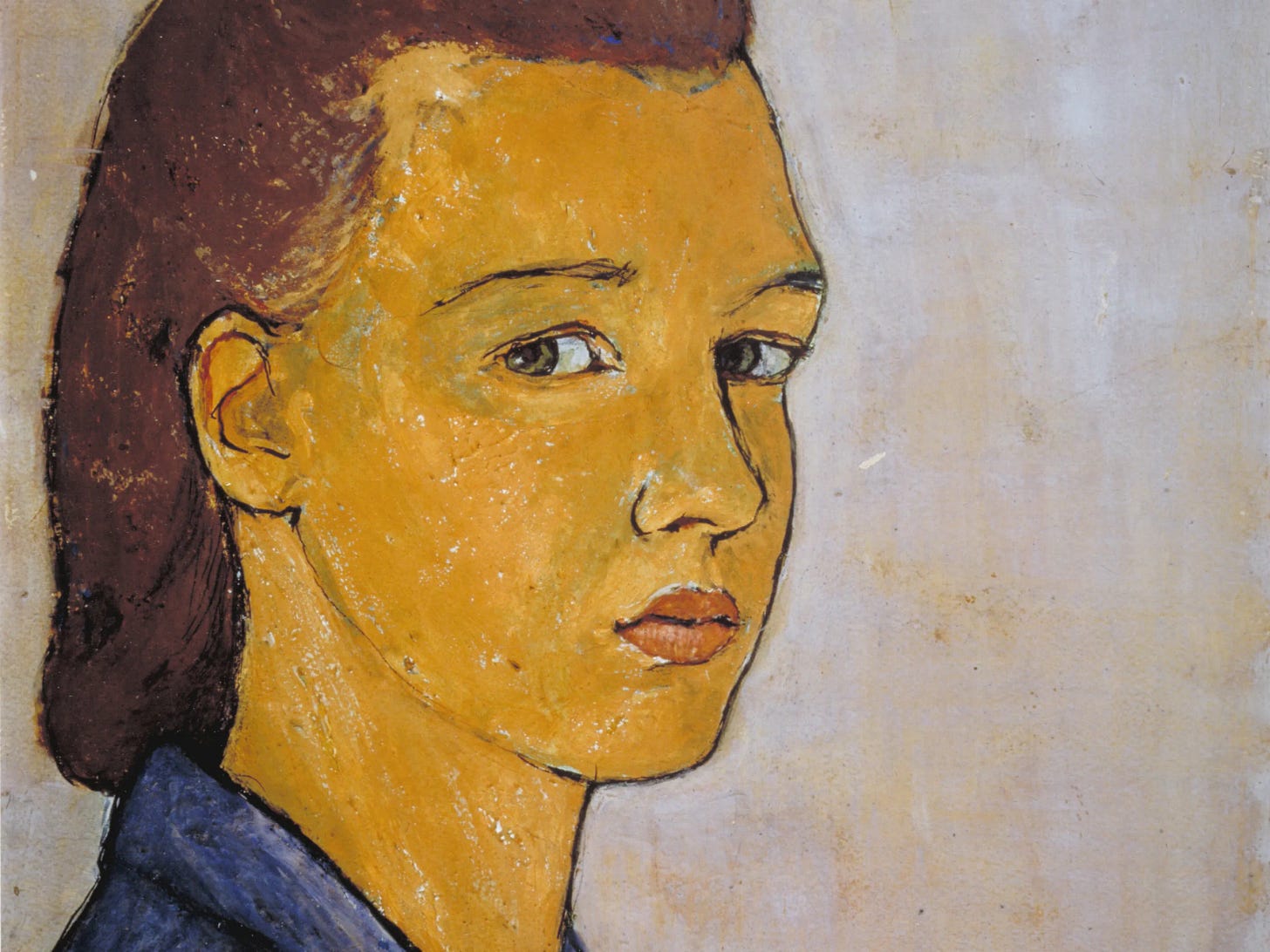

Charlotte Salomon is (regrettably) under-appreciated in today’s modern art discussion, and as a result, many have never heard of her. For those of you who are unfamiliar with her work, the following is a brief synopsis of her life, pulled from the introduction of my thesis (but you can get an even better taste of her life and her art by viewing the online version of her work presented by the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam, and all images of her paintings included here are pulled from this online exhibition):

Charlotte Salomon was born in Berlin in 1917 to an upper middle class Jewish family. For the most part, her childhood was happy, featuring vacations to the sea and the mountains, gymnastics classes, and toys at Christmastime. She showed an aptitude for art, and was given drawing and painting lessons. Underlying the charm of her childhood, though, were dark family secrets. On her maternal side, there was a long history of depression and suicide; almost all of her grandmother’s side of the family committed suicide. And when Charlotte was ten, her mother, too, killed herself, although at the time Charlotte was told she died of influenza.

This domestic tragedy was set against the backdrop of an impending world war: during Charlotte’s teenage years, the Nazis rose to power in Germany. Her father was removed from his prestigious position as a surgeon and his professorship, and was sent to a concentration camp. Charlotte went from being the only Jewish student at the Berlin Art Academy to having her enrollment withdrawn due to mounting anti-semitism. After Kristallnacht, the family decided to flee Germany, and Charlotte was sent to stay with her grandparents in the south of France. There she was supposed to safely wait out the war.

However, the outbreak of WWII overwhelmed Charlotte’s grandmother; she had already endured the loss of both of her children and almost all of her family besides her granddaughter, all the while struggling herself with severe depression, and the news of the persecution of Jewish people led her to become suicidal. When her grandmother eventually attempts suicide, her grandfather finally reveals to Charlotte the truth about the history of suicide in her family, and she learns for the first time the true cause of her mother’s death, as well as the suicides of her namesake aunt Charlotte, great grandmother, great uncle, and grandmother’s nephew. And despite Charlotte’s greatest efforts to nurse her grandmother back to health, she, too, ultimately commits suicide, and Charlotte is left alone with her grandfather. Their relationship is extremely frayed, and there are strong insinuations of sexual abuse by him indicated throughout Charlotte’s artistic ouevre.

Ostensibly to seek refuge from her grandfather, Charlotte rented a small room in the beautiful peninsula off the coast of Nice: Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. There, she embarked on a remarkable project, driven by "the question: whether to take her own life or undertake something wildly unusual.” In the space of just two years, Salomon created over 1000 paintings. Her final work was a series of some 769 hand-selected gouache paintings, chronicling her life in cinematic, narrative scenes complete with dialogue and text overlay, and set to music. She titled the gesamtkunstwerk Leben? oder Theater?: Ein Singspiel (Life? or Theatre?: a song-play) and it is the work for which she is most known today.

After completing Leben? oder Theater? and entrusting it to a local Villefranche doctor, saying “keep this safe, it is my whole life” and dedicating it to Ottilie Moore, her benefactor and protector, Salomon returned to her grandfather in Nice, as her residence permit depended on her being his caretaker. However, she hated being with him, and, in a later-discovered 35-page letter — and whether or not this is artistic dramatization is still unknown — Charlotte confesses to murdering him with a veronal omelette. She addends a portrait of him to the letter, which she created as he allegedly dies in front of her. Scholars debate whether this event is fictive or real, but regardless, her grandfather died in 1942, and Charlotte is then left on her own.

In 1943, as the Nazis were intensifying their search for Jewish people in the south of France, Charlotte Salomon married another German-Jewish refugee named Alexander Nagle. However, tragically their marriage certificate exposed their Jewish identity and they were promptly captured and transported to Drancy internment camp, and then on to Auschwitz, where Charlotte was likely gassed upon arrival at age 26. She was five-months pregnant at the time.

This autobiographical knowledge is usually as far as people go when learning about Charlotte Salomon. Admittedly, her life story is remarkable and tragic, but these details about her life more often than not overshadow her work itself. And Leben? oder Theater? is much more than a simple artistic retelling of a dramatic life — it’s even more than a beautiful historical document (although it certainly is that, too). Rather, Leben? oder Theater? is a complex, innovative, cerebral, and deeply moving exemplar of modern art. It’s a tour de force that is just beginning to get the recognition it deserves, and here I hope to explore some of the many implications of encountering Salomon’s great message in a bottle.

While exploring Salomon’s art in my thesis was a very meaningful experience for me — especially considering the time in which I was working on it, during the coronavirus lockdown in 2020, a time of loss and grief and global change — the experience of seeing where Charlotte actually created her work was perhaps even more meaningful. The main thing I took away from Charlotte’s work was an ardent belief in life, and when I got to Nice, the inspiration behind this affirmation of life in the face of death became even clearer to me.

Nice is a place that is seeped in the light and colors of the sea. The old buildings throughout the city are painted shades of yellow, terracotta and turquoise, as if to mirror the sea and sky; the ocean that hugs them is a deep cerulean. It’s no wonder that Henri Matisse, who was painting in Nice at the time when Charlotte lived there, created his best work there — the iconic blues of his paintings seem to be soaked straight out of the fabric of this magical city. He was an artist that captured the light of the place that inspired him, the same place that so moved Charlotte.

When I got to Nice, I decided to look for the hotel where Charlotte spent two years creating Life? Or Theatre?. After busing into Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat from Nice, I wandered around the beautiful peninsula for about two hours before stumbling upon the little white hotel on a hill overlooking the ocean — the place where Charlotte lived when she was painting.

The hotel had been remodeled and re-named, but the area around it remained relatively unchanged, at least from what I could determine based on old photographs. After studying, grappling with and living with Charlotte’s oeuvre for such a long time, it was surreal to see the place that had inspired it all.

I eagerly walked into the lobby, hoping to see an original collection of Charlotte's work, and maybe even get the chance to see her old room. As I approached the concierge desk, I noticed a small display of prints from Life? Or Theatre? and a plaque, but almost no other indication that Charlotte had ever even been there. And when I asked the concierge if I could see her room, he responded that he had never heard of Charlotte Salomon, and seemed surprised when I pointed out the display behind his desk, as if he had never noticed it before.

I left the hotel disappointed, and began to journey back along the winding pathways of the peninsula that jut up against the sea. It was frustrating to see that Charlotte’s presence had been erased, save for a minor trace, as if what she had created didn’t make a difference, didn’t matter at all. But then my attention was captured by the sunset, and I stopped walking. As I watched the sun melt over the water, a deep peace came over me. In that moment, I could easily see what would prompt someone to try and capture this light — the golden light of the Côte d’Azur — despite the inherent futility of such an endeavor, especially given the artist’s circumstances.

The overlay Charlotte scribbled for the above painting, set in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, reads like a poem:

High on a cliff grow pepper trees - softly the wind stirs the small silvery leaves. Far below, foam eddies and melts in the infinite span of the sea. Foam, dreams - my dreams on a blue surface. What makes you shape and reshape yourselves so brightly from so much pain and suffering? Who gave you the right? Dream, speak to me - whose lackey are you? Why are you rescuing me? High upon a cliff grow pepper trees. Softly the wind stirs the small silvery leaves.

In that moment above the sea, I realized that even if people have forgotten her, or never knew about her in the first place, the fact that she tried to capture the light mattered. And she probably seemed crazy for doing so — just like the man in the park in Madrid who was trying to fill a plastic bag with sunlight probably seemed crazy to anyone else who saw him. But I believe that if you notice beauty or light, and you love it so much that you make art to capture it, you are doing work that matters. Even if you reach just one person, you are helping them by sharing your moments of inspiration.

The fact that Charlotte tried to capture the light in order to create Life? Or Theatre? matters — it mattered then and it still matters now, because her efforts allowed her to transmit that light to all who later encountered her art; she certainly transmitted it to me. Life? Or Theatre? is a preserved vessel of light from a place that all but forces you to believe in life.

So maybe precisely as a result of — rather than in spite of — Charlotte Salomon having the audacity to paint while looking death in the eye, when we ourselves encounter the portal that is Leben? oder Theatre?, we, too, are entering into a capturing of the light and a rediscovery of life, with every turn of the page.